For more than 2,000 years, the Maya constructed some of the most visually stunning cities in history. Their monumental pyramids thrust through the thick jungle canopy and their astronomers mapped the movement of planets with remarkable precision, while their artists produced works that still leave us breathless. Then, seemingly overnight, they vanished. Full of people: Hundreds of thousands of them, bustling in these massive cities that were now stone and vine and the limbs of ancient trees in Central America.

What happened to the Maya has long been a mystery that has perplexed archaeologists, historians and curiosity seekers for more than century. Was it something that was happening in one horrendous moment? Did invaders destroy their civilization? Or was something more complex and terrifying afoot? The response, as scholars have learned, is a lot more interesting — and pertinent to our time — than anyone could have guessed. This isn’t just ancient history. It’s a warning chiseled in stone, for us to decipher.

Who Were the Maya, and Why Does Their Fall Matter?

Before we delve into what killed Mayan culture, let’s first consider what made them so incredible. The Maya were not one empire, as Rome was. They were a series of city-states that covered what we now term as Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, Honduras and El Salvador. Each town was led by its own ruler, frequently at war with or making alliances with neighbours, comparable to the city-states of ancient Greece.

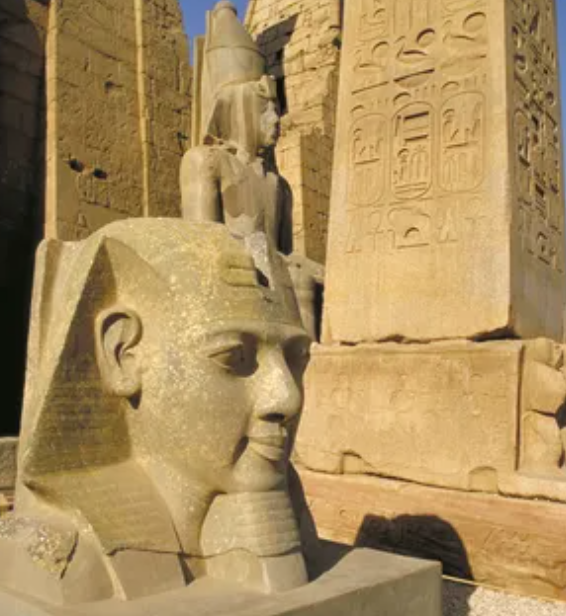

These were not our primitive village dwellers. Mayan cities such as Tikal, Palenque and Copán were architectural wonders. At its height, Tikal alone was home to between 100,000 and 200,000 people — about the size of present-day Salt Lake City in Utah. Their pyramids rose more than 200 feet high, all constructed without metal tools, wheels or pack animals.

The Maya devised the most sophisticated writing system in the Americas, developed accurate calendars that could tell time over spans of many millennia and made precise astronomical calculations that have since been corroborated by satellites. They knew the length of a solar year, to within minutes. They predicted eclipses. They were able to follow Venus’s travel across the sky with breathtaking precision.

But something went terribly wrong around 900 CE. The grand cities of the southern Maya lowlands were deserted in only 150 years. And population estimates indicate that millions died or fled. It’s one of the biggest mysteries in history — and it has taken decades to solve.

The Old Theories: What Historians Got Wrong

Simple explanations for what happened to the Maya were batted around for years after Stephens’ book was published. Each theory was clean and tidy, a bow tied on the package. But, alas, real history is hardly ever so tidy.

The Invasion Theory

Some early researchers suspected that foreign invaders roamed Mayan lands, toppling cities and butchering the people. The evidence? Some sites appeared to have been burnt and destroyed. But there’s a catch: no archaeological evidence for such an invasion. No foreign weapons, no distinctive pottery from outsiders, no mass graves indicating genocide. This theory is just full of holes.

The Disease Theory

Perhaps a pandemic wiped them out? As I said, diseases have been known to bring civilizations crashing down. A third of Europe’s population was killed by the Black Death in the 14th century. But, again, the evidence doesn’t bear this out for the Maya. Disease epidemics impart unmistakeable signatures in skeletal remains and burial practices. No evidence of a civilization-ending plague has been found by archaeologists during the collapse period.

The Single Disaster Theory

Maybe it was a volcanic eruption, or an enormous earthquake? Undoubtedly natural disasters caused disruption of Mayan polities over the centuries, they wrote, but no single disaster is that is geographically widespread or precisely dated to explain what happened. The abandonment occurred piece by piece over more than a century and reached cities hundreds of miles apart.

These simple explanations did not work, since they depended on one thing bringing the building down. It turns out that reality, according to more recent research, was much more complicated — and terrifying.

Climate Change: The Smoking Gun

Scientists made a breakthrough in the 1990s and early 2000s. Using advanced methods for analyzing sediment cores from lakes and caves in Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula, they reconstructed the rainfall there back through the ages. What they discovered was shocking.

The Mayan heartland suffered severe droughts in the years 800-1000 CE—its most intense arid period of the past several millennia. These weren’t short dry spells. We’re not talking about years with half as much rainfall or droughts, but rather decades long ones that brought 40-50% less rain than normal years.

To put this in some perspective, imagine if half the typical annual rainfall of your city suddenly stopped falling. Gardens would wither. Rivers would run dry. Reservoirs would empty. Then let that be not for a season but your whole childhood, your parents’ middle age and their retirement. That’s what the Maya faced.

Evidence from the Earth Itself

How do scientists know this? A wide range of diverse methods are all converging on a single conclusion:

Stalagmites form in layers, like tree rings. Analysis of these layers can tell us about rainfall levels hundreds of years ago. Stalagmite records from caves in Guatemala reveal extreme drying at the time of collapse.

Sediment cores of lakes are the mud-written tales. Some minerals and chemicals accumulate differently based on rainfall. Studies of Lake Chichancanab in Mexico reveal both severe drought and drying, consistent with the timing of its collapse.

Tree ring readings from the ancient wood found at Mayan sites also bears this out, providing evidence of long-term reductions in rainfall.

All of the evidence is both overwhelming and consistent. The Maya confronted an environmental disaster that would put even modern civilization to the test.

Deforestation: How the Maya Ruined Their Own Civilization

Here is where the story becomes truly cautionary. The Maya weren’t just unlucky with the weather. They made their own problems significantly worse by mismanaging their environment.

Cities with a population of 100k+ take tremendous resources to build and upkeep. There weren’t enough bricks, stones and other building materials for the thousands of pyramids, palaces and plazas perched around the lakes. The Maya cleared huge swaths of forests in order to:

- Mix plaster for construction (burning limestone used a lot of wood)

- Clear land for agricultural use to help support expanding populations

- Supply wood for the fire to cook and hold ceremonies

- Make space for expanding cities

And now the Mayans’ achievements are matched by modern archaeological science using LiDAR technology (lasers that can see through jungle foliage), which has shown the true extent of their civilization. They have discovered many more structured objects than were previously known, pointing to population densities much higher than once thought. The more people, the greater the environmental pressure.

Deforestation triggers a vicious cycle. Bare of trees, soil erodes readily. Nutrients wash away. The land loses productivity, so even more land must be cleared to produce the same amount of food. Clearing forests likewise diminishes rainfall by altering local climate patterns — trees are involved in rain production through a process called transpiration.

Soil studies also demonstrate that there was high erosion during the Classic Maya. The Maya were quite literally watching their agricultural base dry up, while droughts made water even more scarce.

Warfare: Fighting Over Scraps

As resources ran out, Mayan city-states began to war viciously with one another. Competition over water, farmland and trade routes rose. Archaeological evidence shows that warfare increased significantly in the 8th and 9th century.

The Evidence of Violence

- Walls were erected around open cities

- Interest in scenes of battle and victim suffering expanded

- Mass graves that are believed to contain warriors have been found in the archaeological record

- Hills and tactical features were turned into fortified positions

- The hieroglyphic inscriptions of this time refer with especial frequency to warfare

One revealing case study is the conflict between Tikal and Calakmul, Mayan superpowers. Their clash embroiled many smaller cities in a destructive cycle of raids, counter-raids and shifting alliances. Picture desperately needed resources for water management and agriculture being used instead to pay for weapons and fortifications.

This warfare wasn’t why that order fell apart — it was a symptom of deeper problems. But it definitely hastened the decline.

Falling Kingdoms: When Kings Lose Their Power

Mayan kings were more than just political leaders, they were divine intermediaries between people and gods. Their legitimacy was founded on their control over rain, good harvests and cosmic harmony. And they made religious and sacrificial ceremonies of great complexity to the gods who would reward them by making their people successful.

But what if the rain doesn’t come, no matter how many ceremonies a king performs? If harvests fail year after year, despite all the prayers and bloodletting rituals.

People lose faith. Their complex religious and political system, which united the Mayan people, started to collapse. Evidence suggests that:

- Building of new temples and palaces began to slow down

- Royal inscriptions and monuments declined in numbers

- Some rulers were deposed or abandoned, it seems

- Trade networks were too complex and broke down which tied cities in various parts of the world together

- The production of luxury goods by artisans plunged

The later date could mark the final cessation of major inscriptions in many sites, because central authorities seem to have died out around this time. Without good leadership and with religious institutions failing to produce results, the social glue holding people to dying cities came apart.

The Perfect Storm: When Everything Comes Together

The Mayan collapse had no single cause — it was a cascade of connected events, the Rube Goldberg machine of ancient history. Here’s what the pieces would look like:

| Problem | Direct Impacts | Cascade Effects |

|---|---|---|

| Long-Term Drought | Water and Crop shortages | Starvation; Population stress |

| Deforestation | Soil erosion, Less Rain | Lower Farm output |

| Food Scarcity | Malnutrition + Illness | Weaker Pops; Higher mortality; Lower pace of birth |

| Resource Rivalry | City-vs-City War | Destruction, Drained resources |

| Political Catastrophe | Central-Desk Loss | Social Collapse + Move |

| Economic Fall | Trade Slowdown | Less Resources |

| Cultural Drop | – | – |

One problem reinforced the others. Drought stressed agriculture. Agricultural failure undermined political authority. Political instability led to warfare. Infrastructure to manage water and to grow food was destroyed in the warfare. It was a death spiral.

The Maya were not stupid, and they were not primitive. They were sophisticated people in an impossible situation. Their civilization had become too big, too networked, to quickly adjust when the environment pushed back.

Why Some Lived and Others Disappeared

This is part that people tend to overlook: some Maya did not disappear. Those southern lowland cities were the hardest hit by the collapse: places such as Tikal, Copán and Palenque. But the Mayan civilization survived in other areas, most notably the northern Yucatan Peninsula.

Cities such as Chichen Itza and later Mayapan flourished for several centuries following the southern abandonment. Why? They had a few things going in their favor:

Better Water Management

Northern cities were closer to cenotes — natural sinkholes that supplied reliable water even during dry years. They were less dependent on seasonal rain held in reservoirs.

Different Agricultural Strategies

Northern Maya depended more on a variety of crops and different farming practices that were less sensitive to drought. They weren’t as wedded to the idea of water-intensive maize monoculture.

Flexibility and Adaptation

Some of those that survived were marked by political reorganization. They developed alternative systems of government that relied less on an individual king’s performance of religious rituals.

Whatever surviving Maya did, they did it by adjusting to new realities. Those who could not or would not adapt vanished into history.

Lessons for Our Modern World

The fall of the Mayan civilization isn’t just ancient history — it is a looking glass through which we can see our present-day predicament. The mirrors between their circumstances and our present dilemmas are disquieting:

Climate Pressure

The Maya were subject to natural climate variation. We confront human-caused climate change likely to become orders of magnitude more severe. Already, regions around the world suffer from more frequent droughts, flooding and weather extremes.

Environmental Degradation

We’re trashing the environmental systems that also offer us life support, like the Maya. Productivity in agriculture is also under pressure from deforestation, soil degradation and water pollution, as well as biodiversity loss.

Resource Competition

The more there are fewer resources, the harder we fight for them. Water rights are contentious throughout the American West, as well as, for example, the Middle East and Central Asia. Climate refugees are people who escape areas where the resources they need to live in a healthy way can no longer exist.

Complex, Fragile Systems

Today, civilization does not operate locally but rather across advanced supply networks that stretch around the globe, where technology plays a major role in the various trading systems. They are efficient but brittle. One breakdown has a snowball effect throughout the system.

Population Pressure

The Maya had preindustrial agriculture and millions of people to feed. We have billions who depend on systems that depend on fossil fuels, a stable climate and functioning global cooperation.

The Maya were themselves unable to foresee or prevent the droughts that befell them. We have no such excuse. Scientists have been sounding the alarm on climate change for decades. We can see what’s coming.

The question is, will we react any differently than did the Maya, or will the archaeologists of the future wonder why we made no effort to reverse our own self-destruction now that the outlines are clear?

What Happened to the People?

When we say Mayan cities “collapsed,” it doesn’t mean everyone died. Most people were safe — they just had to go away. There are a few possibilities, according to archaeological and genetic studies:

Others of the Maya moved to cities farther north with more resources and better access to water. Others scattered into small rural hamlets less reliant on sophisticated infrastructure. Ninety percent of the population of the southern lowlands is thought to have vanished, but those people had to go somewhere.

Descendants of the Maya continue to inhabit all parts of Central America today. Millions of people in places like Guatemala, Mexico and other countries speak Mayan languages as their first tongue, doing so while maintaining traditions thousands of years old. The civilization crumbled, but the people survived — they just had to leave behind their greatest accomplishments.

Just think of the last generation to have lived in Tikal. The monuments of your great-grandparents crowd you, the temples where your ancestors found salvation weigh down around you, plazas once filled with traders at markets held for cities three days’ distant. Now the population has dwindled. Buildings crumble from neglect. The water reservoirs are dry. Food is scarce. Your king prays year after year to the gods, but they do not answer him.

And, finally, you decide to leave and break your heart. You grab what you can carry and walk away from everything your people have spent centuries building. A few generations later, the jungle has reclaimed everything and your once glorious city is nothing more than a legend that someone whispers to their children at bedtime in your bloodline.

That, right there, is the human tragedy hiding in the archaeological data.

Frequently Asked Questions

Did the Maya completely disappear?

No. The Classic Maya civilization fell, which is to say that its large city-states and intricate political systems failed. But the Maya people survived. Today about 7 million Maya people live in Mexico and Central America, preserving their languages and cultural traditions.

How long did the fall take?

The unraveling was not one event, but a process that stretched out over 150-200 years, from approximately 800 to 950 CE. Fall occurred at various times in different cities. Some were vacated abruptly, while others declined more gradually.

Might the Maya have avoided their downfall?

Possibly, with different choices. Had they practiced more sustainable forestry, better water conservation or applied birth control to population booms, they may have weathered the droughts. But they did not possess the scientific knowledge we do today about managing ecosystems and understanding climate patterns.

What had led to the collapse?

There wasn’t one single cause. The collapse occurred for a combination of reasons: prolonged drought, environmental degradation due to massive deforestation, ramped-up warfare, crop failure and political disintegration. These issues fed into each other in a negative feedback loop.

Did any similar civilizations fall for similar reasons?

Yes. The Akkadian Empire (2200 BCE), the Ancestral Puebloans of the American Southwest (1300 CE) and the Khmer empire at Angkor (1400s CE) all are rumored to have collapsed due in part to climate-induced environmental degradation. We have many historical examples of civilizations that did not adapt to environmental challenges.

What can today’s world learn from the Maya collapse?

Farmers in Mayan times show how deforestation and resource competition can unravel even advanced civilizations. They demonstrate the consequences of disregard for environmental limits. They also demonstrate that adaptation is possible — those who adapted and shifted their strategies made it through.

Tomorrow: By Writing Our Own Ending

The tale of the collapse of Mayan civilization raises uncomfortable questions about our own future. We are living at a time of rapid environmental change, pressure on resources and global issues that demand an unprecedented level of cooperation.

The Maya couldn’t see how they were going to end. They had no climate science, global communications or knowledge of other civilizations’ mistakes to learn from. We have all these advantages — if we can bring them to bear.

Their empty cities are memorials to human accomplishment and overreach. It was the same intelligence that had constructed Tikal’s soaring pyramids, and yet failed to understand their world’s constraints in time. We shouldn’t feel superior. We should feel warned.

The Maya inscribed their story in stone and jade, in the very seams of their pyramids and the graceful queues of their hieroglyphs. That story ends in empty cities overgrown with jungle, a cautionary tale sitting there waiting for us to learn and understand.

What story will we write? Would our distant descendants examine our ruins and ask how we could have ignored the warning signs? Or will we be the first civilization to learn from history in time, adapt before disaster is upon us and create a sustainable model for both living on this planet and moving beyond it?

Our story has no written ending. The Maya can’t alter their destiny, but we can. The question is whether we have the wisdom and courage to make better choices than they did. Their collapse is history. Ours doesn’t have to be.

The simple truth about the Maya collapse is not only what happened to them. It is about what could happen to us — and, crucially, what we can do about it while there’s still time.